A prominent position in the Elected Rada was occupied by Duma nobleman A.F. Adashev, court priest Sylvester, Metropolitan Macarius, Duma clerk I.M. Viskovaty, Prince A.M. Kurbsky. I.r. (Council of the Elected) used book. A. Kurbsky in the History of the Grand Duke of Moscow. Massive anti-feud.

The Russian state at the end of the 1540-1550s. The Elected Rada included those close to Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible. In foreign policy, the attention of the Chosen Slave was initially focused on the east (the annexation of the Kazan and Astrakhan khanates), and later began to be occupied by the struggle for the Baltic states. The importance of Sylvester and Adashev at court also created enemies for them, of which the main ones were the Zakharyins, relatives of Queen Anastasia.

The Rada discussed plans for government reforms and foreign policy and supervised their implementation. Some participants of the I. r. became close to the opposition boyars who opposed the continuation of the Livonian War of 1558-83 (See Livonian War of 1558-83). THE ELECTED RADA - a circle of people close to Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible, in fact a former unofficial. 40 50s 16th century Polish Ivan found in them, as well as in Tsarina Anastasia Romanovna and Metropolitan Macarius, moral support and support and directed his thoughts for the good of Russia.

Having become dangerously ill, the tsar wrote a spiritual letter and demanded that his cousin, Prince Vladimir Andreevich Staritsky, and the boyars swear allegiance to his son, the infant Dmitry. But Vladimir Andreevich refused to take the oath, asserting his own rights to the throne after the death of John and trying to form a party for himself.

Correspondence between Andrei Kurbsky and Ivan the Terrible

John recovered and began to look at his former friends with different eyes. Likewise, Sylvester’s supporters had now lost the favor of Queen Anastasia, who could suspect them of not wanting to see her son on the throne. Natural death saved him from royal reprisals, since in the coming years all of Adashev’s relatives were executed.

Usachev A. S. Chronicler of the beginning of the kingdom and the metropolitan see in the middle of the 16th century. // Problems of Russian history and historiography of the 17th-20th centuries: a collection of articles dedicated to the 60th anniversary of Ya. G. Solodkin. One brother of the late sovereign, Yuri, was imprisoned on suspicion and starved there. Another brother, Andrei, frightened of the same fate, ran away; for the sake of his own salvation, he plotted an uprising, but was captured and strangled; his wife and son were thrown into prison.

Elena's uncle, Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky, began to reproach his niece for her relationship with Telepnev; for this he was imprisoned and starved to death. His sister Agrafena was shackled and thrown into prison. The young sovereign turned thirteen in 1544. He was influenced by Elena's brothers: Yuri and Mikhail Vasilyevich Glinsky.

At the instigation of his uncles, the youth Ivan ordered Andrei Shuisky to be seized and given to his hounds, who immediately tore him to pieces. Fyodor Skopin-Shuisky and other boyars of his party were exiled. His wanderings around the Russian land, both pious and sinful, had a heavy impact on the inhabitants. Meanwhile, having tasted blood on Shuisky, he gained a taste for it, and the Glinskys took advantage of this and incited him to give free rein to his impressionable nature.

They said that Vladimir Monomakh bequeathed these regalia to his son Yuri Dolgoruky and ordered them to be kept from generation to generation until God erects a worthy autocrat in Rus'.

At the beginning of 1547, by order of the tsar, girls were collected from all over the state, and the young tsar chose from them the daughter of the deceased okolnik Roman Yuryevich Zakharyin. His relatives, the Glinskys, were in charge of everything, their governors sat everywhere, there was no justice anywhere, violence and robberies took place everywhere. Ivan Vasilyevich did not like this so much that he ordered the Pskovites to be undressed, laid on the ground, poured with hot wine and burned with candles on their hair and beards.

The compromise policy of the Elected Rada in the sphere of extending the rights and privileges of the boyars to the nobles, despite the inconsistency, was beneficial to the nobility. From that time on, the tsar, averse to noble boyars, brought closer to himself two unborn, but the best people of his time, Sylvester and Adashev.

To paraphrase the great thinker, we can say that the entire history of mankind has been a history of betrayals. Since the birth of the first states and even earlier, individuals appeared who, for personal reasons, went over to the side of the enemies of their fellow tribesmen.

Russia is no exception to the rule. Our ancestors’ attitude towards traitors was much less tolerant than that of their advanced European neighbors, but even here there were always enough people ready to go over to the side of the enemy.

Prince Andrei Dmitrievich Kurbsky Among the traitors of Russia he stands apart. Perhaps he was the first of the traitors who tried to provide an ideological justification for his action. Moreover, Prince Kurbsky presented this justification not to anyone, but to the monarch whom he betrayed - Ivan the Terrible.

Prince Andrei Kurbsky was born in 1528. The Kurbsky family separated from the branch of Yaroslavl princes in the 15th century. According to the family legend, the clan received its surname from the village of Kurba.

The Kurbsky princes proved themselves well in military service, participating in almost all wars and campaigns. The Kurbskys had a much more difficult time with political intrigues - the ancestors of Prince Andrei, participating in the struggle for the throne, several times found themselves on the side of those who later suffered defeat. As a result, the Kurbskys played a much less important role at court than might be expected given their origin.

Brave and daring

The young Prince Kurbsky did not rely on his origins and intended to gain fame, wealth and honor in battle.

In 1549, 21-year-old Prince Andrei, with the rank of steward, took part in the second campaign of Tsar Ivan the Terrible against the Kazan Khanate, having proven himself to be the best.

Soon after returning from the Kazan campaign, the prince was sent to the province of Pronsk, where he guarded the southwestern borders from Tatar raids.

Very quickly, Prince Kurbsky won the sympathy of the Tsar. This was also facilitated by the fact that they were almost the same age: Ivan the Terrible was only two years younger than the brave prince.

Kurbsky begins to be entrusted with matters of national importance, which he copes with successfully.

In 1552, the Russian army set off on a new campaign against Kazan, and at that moment a raid on Russian lands was made by the Crimean Khan Davlet Giray. Part of the Russian army, led by Andrei Kurbsky, was sent to meet the nomads. Having learned about this, Davlet Giray, who reached Tula, wanted to avoid meeting with the Russian regiments, but was overtaken and defeated. When repelling the attack of the nomads, Andrei Kurbsky especially distinguished himself.

Hero of the assault on Kazan

The prince showed enviable courage: despite serious wounds received in battle, he soon joined the main Russian army marching towards Kazan.

During the storming of Kazan on October 2, 1552, Kurbsky, together with Voivode Peter Shchenyatev command the regiment of the right hand. Prince Andrei led the attack on the Yelabugin Gate and, in a bloody battle, completed the task, depriving the Tatars of the opportunity to retreat from the city after the main forces of the Russians burst into it. Later, Kurbsky led the pursuit and defeat of those remnants of the Tatar army that nevertheless managed to escape from the city.

And again in battle the prince demonstrated personal courage, crashing into a crowd of enemies. At some point, Kurbsky collapsed along with his horse: both friends and strangers considered him dead. The governor woke up only some time later, when they were about to take him away from the battlefield in order to bury him with dignity.

After the capture of Kazan, the 24-year-old Prince Kurbsky became not just a prominent Russian military leader, but also a close associate of the Tsar, who gained special trust in him. The prince entered the monarch's inner circle and had the opportunity to influence the most important government decisions.

In the inner circle

Kurbsky joined the supporters priest Sylvester and okolnichy Alexei Adashev, the most influential persons at the court of Ivan the Terrible in the first period of his reign.

Later, in his notes, the prince would call Sylvester, Adashev and other close associates of the tsar who influenced his decisions the “Chosen Rada” and would in every possible way defend the necessity and effectiveness of such a management system in Russia.

In the spring of 1553, Ivan the Terrible became seriously ill, and the life of the monarch was threatened. The tsar sought an oath of allegiance to his young son from the boyars, but those close to him, including Adashev and Sylvester, refused. Kurbsky, however, was among those who did not intend to resist the will of Ivan the Terrible, which contributed to the strengthening of the prince’s position after the king’s recovery.

In 1556, Andrei Kurbsky, a successful governor and close friend of Ivan IV, was granted a boyar status.

Under threat of reprisals

In 1558, with the beginning of the Livonian War, Prince Kurbsky took part in the most important operations of the Russian army. In 1560, Ivan the Terrible appointed the prince commander of the Russian troops in Livonia, and he won a number of brilliant victories.

Even after several failures of Voivode Kurbsky in 1562, the tsar’s trust in him was not shaken; he was still at the peak of his power.

However, changes are taking place in the capital at this time that frighten the prince. Sylvester and Adashev lose influence and find themselves in disgrace; persecution begins against their supporters, leading to executions. Kurbsky, who belonged to the defeated court party, knowing the character of the tsar, begins to fear for his safety.

According to historians, these fears were unfounded. Ivan the Terrible did not identify Kurbsky with Sylvester and Adashev and retained confidence in him. True, this does not mean at all that the king could not subsequently reconsider his decision.

Escape

The decision to flee was not spontaneous for Prince Kurbsky. Later, the Polish descendants of the defector published his correspondence, from which it followed that he had been negotiating with Polish King Sigismund II about going over to his side. One of the governors of the Polish king made a corresponding proposal to Kurbsky, and the prince, having secured significant guarantees, accepted it.

In 1563, Prince Kurbsky, accompanied by several dozen associates, but leaving his wife and other relatives in Russia, crossed the border. He had 30 ducats, 300 gold, 500 silver thalers and 44 Moscow rubles. These valuables, however, were taken away by the Lithuanian guards, and the Russian dignitary himself was placed under arrest.

Soon, however, the misunderstanding was resolved - on the personal instructions of Sigismund II, the defector was released and brought to him.

The king fulfilled all his promises - in 1564, extensive estates in Lithuania and Volhynia were transferred to the prince. And subsequently, when representatives of the gentry made complaints against the “Russian,” Sigismund invariably rejected them, explaining that the lands granted to Prince Kurbsky were transferred for important state reasons.

Relatives paid for the betrayal

Prince Kurbsky honestly thanked his benefactor. The fugitive Russian military leader provided invaluable assistance, revealing many secrets of the Russian army, which ensured that the Lithuanians carried out a number of successful operations.

Moreover, starting in the autumn of 1564, he personally participated in operations against Russian troops and even put forward plans for a campaign against Moscow, which, however, were not supported.

For Ivan the Terrible, the flight of Prince Kurbsky was a terrible blow. His morbid suspicion received visible confirmation - it was not just a military leader who betrayed him, but a close friend.

The Tsar brought down repression on the entire Kurbsky family. The traitor's wife, his brothers, who served Russia faithfully, and other relatives who were completely uninvolved in the betrayal suffered. It is possible that Andrei Kurbsky’s betrayal also influenced the intensification of repression throughout the country. The lands that belonged to the prince in Russia were confiscated in favor of the treasury.

Five letters

A special place in this history is occupied by the correspondence between Ivan the Terrible and Prince Kurbsky, which lasted for 15 years from 1564 to 1579. The correspondence includes only five letters - three written by the prince and two written by the king. The first two letters were written in 1564, shortly after Kurbsky's flight, then the correspondence was interrupted and continued more than a decade later.

There is no doubt that Ivan IV and Andrei Kurbsky were smart and educated people for their time, therefore their correspondence is not a continuous set of mutual insults, but a real discussion on the issue of ways to develop the state.

Kurbsky, who initiated the correspondence, accuses Ivan the Terrible of destroying state foundations, authoritarianism, and violence against representatives of the propertied classes and the peasantry. The prince speaks out in support of limiting the rights of the monarch and creating an advisory body under him, the “Elected Rada”, that is, he considers the most effective system that was established during the first periods of the reign of Ivan the Terrible.

The Tsar, in turn, insists on autocracy as the only possible form of government, referring to the “divine” establishment of such an order of things. Ivan the Terrible quotes the Apostle Paul that everyone who resists authority resists God.

Actions are more important than words

For the tsar, this was a search for justification for the most cruel, bloody methods of strengthening autocratic power, and for Andrei Kurbsky, it was a search for justification for the perfect betrayal.

Both of them, of course, were lying. The bloody actions of Ivan the Terrible could not always be somehow justified by state interests; sometimes the outrages of the guardsmen turned into violence in the name of violence.

Prince Kurbsky's thoughts about the ideal state structure and the need to take care of the common people were just an empty theory. The prince's contemporaries noted that the ruthlessness towards the lower class characteristic of that era was inherent in Kurbsky both in Russia and in the Polish lands.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Prince Kurbsky beat his wife and was involved in racketeering

Less than a few years later, the former Russian governor, having joined the ranks of the gentry, began to actively participate in internecine conflicts, trying to seize the lands of his neighbors. Replenishing his own treasury, Kurbsky traded in what is now called racketeering and hostage-taking. The prince tortured rich merchants who did not want to pay for their freedom without any remorse.

Having grieved over his wife who died in Russia, the prince was married twice in Poland, and his first marriage in the new country ended in a scandal, because his wife accused him of beating him.

Second marriage to Volyn noblewoman Alexandra Semashko was more successful, and from him the prince had a son and daughter. Dmitry Andreevich Kurbsky, born a year before his father's death, subsequently converted to Catholicism and became a prominent statesman in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Prince Andrei Kurbsky died in May 1583 at his estate Milyanovichi near Kovel.

His identity is still hotly debated to this day. Some call him “the first Russian dissident,” pointing to fair criticism of the tsarist government in correspondence with Ivan the Terrible. Others suggest relying not on words, but on deeds - a military leader who during the war went over to the side of the enemy and fought with arms in his hands against his former comrades, devastating the lands of his own Motherland, cannot be considered anything other than a vile traitor.

One thing is clear - unlike Hetman Mazepa, who in modern Ukraine has been elevated to the rank of a hero, Andrei Kurbsky in his homeland will never be among the revered historical figures.

After all, Russians’ attitude towards traitors is still less tolerant than that of their European neighbors.

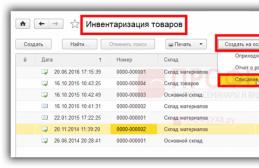

Around 1549, a government circle formed around Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible). He went down in history as Elected Rada. It was a kind of (unofficial) government under the leadership of Alexei Fedorovich Adashev. He himself was one of the Kostroma nobles, and had noble relatives in Moscow. The Elected Rada included:: priest of the court Cathedral of the Annunciation Sylvester, Metropolitan of Moscow and All Rus' Macarius, Prince Kurbsky Andrei Mikhailovich, head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz Viskovaty Ivan Mikhailovich and others.

The prerequisite for the creation of an unofficial government was the unrest of 1547, called the Moscow Uprising. Ivan IV at this time was only 17 years old. The cause of the uprising was the aggravation of social contradictions in the 30-40s. At this time, the arbitrariness of the boyars was very clearly manifested in connection with the early childhood of Ivan IV. The Glinsky princes set the tone, since the mother of the crowned boy was Elena Vasilievna Glinskaya.

There was growing dissatisfaction among the broad masses with taxes, which were unbearable. The impetus for the uprising was a fire in Moscow at the end of the second ten days of June. It was huge in size and caused irreparable damage to the well-being of Muscovites. Embittered people, who had lost all their property, took to the streets of the capital on June 21, 1547.

Rumors spread among the rebels that the city was set on fire by the Glinsky princes. Allegedly, their wives cut out the hearts of the dead, dried them, crushed them, and sprinkled the resulting powder on houses and fences. After this, magic spells were cast and the powder burst into flames. So they set fire to Moscow buildings in which ordinary people lived.

The angry crowd tore to pieces all the Glinsky princes who came to hand. Their estates, which survived the fire, were looted and burned. The indignant people began to look for the young tsar, but he left Moscow and took refuge in the village of Vorobyovo (Sparrow Hills, during the years of Soviet power they were called Lenin Hills). A huge mass of people went to the village and surrounded it on June 29.

The Emperor came out to the people. He behaved calmly and confidently. After much persuasion and promises, he managed to persuade the people to calm down and disperse. People believed the young king. Their indignant ardor died down. The crowd moved to the ashes in order to somehow begin to organize their life.

Meanwhile, by order of Ivan IV, troops were brought to Moscow. They began to arrest the instigators of the uprising. Many of them were executed. Some managed to escape from the capital. But the Glinskys' power was irrevocably undermined. The situation was aggravated by unrest in other Russian cities. All this made it clear to the king that the existing government system was ineffective. That is why he gathered progressive-minded people around him. Life itself and the instinct of self-preservation forced him to do this. Thus, in 1549, the Elected Rada began its work to reform the state structure in the Muscovite kingdom.

Reforms of the Elected Rada

The unofficial government ruled the state on behalf of the king, so its decisions were equated with the royal will. Already in 1550, military reform began to be carried out. Streltsy troops began to form. This was a guard whose task was to protect the sovereign. By analogy, the Streltsy can be compared to the royal musketeers of France. At first there were only 3 thousand people. Over time, the number of archers increased significantly. And Peter I put an end to such military units in 1698. So they existed for almost 150 years.

Order was established in military service. In total, there were two categories of service people. The first category included boyars and nobles. As soon as a boy was born, he was immediately enrolled in military service. And he became suitable for it upon reaching the age of 15 years. That is, all people of noble birth were required to serve in the army or in some other government service. Otherwise, they were considered “underage”, regardless of age. It was a shameful nickname, so everyone served.

The other category included commoners. These are archers, Cossacks, artisans associated with the manufacture of weapons. Such people were called recruited “by appointment” or by recruiting. But the military of those years had nothing in common with today's military personnel. They did not live in barracks, but were allocated plots of land and private houses. Entire military settlements were formed. In them, the servicemen lived a normal, measured life. They sowed, plowed, harvested, got married and raised children. In case of war, the entire male population was put under arms.

Foreigners also served in the Russian army. These were mercenaries, and their number never exceeded a couple of thousand people.

The entire vertical of power was subjected to serious reform. They established strict control over local government. It was not the population but the state that began to support it. A unified state duty was introduced. Now only the state collected it. A single tax per unit area was established for landowners.

The unofficial government also carried out judicial reform. In 1550, a new Code of Law was published - a collection of legislative acts. He regulated cash and in-kind fees from peasants and artisans. Tightened penalties for robbery, robbery and other criminal offenses. Introduced several harsh articles on punishment for bribes.

The elected Rada paid great attention to personnel policy. The so-called Yard Notebook was created. It was a list of sovereign people who could be appointed to various high positions: diplomatic, military, administrative. That is, a person fell into a “clip” and could move from one high post to another, bringing benefit to the state everywhere. Subsequently, this style of work was copied by the communists and created the party nomenklatura.

The central state apparatus was significantly improved. Many new orders (ministries and departments, if translated into modern language) appeared, as the functions of local authorities were transferred to officials of the central apparatus. In addition to national orders, regional ones also emerged. That is, they oversaw certain territories and were responsible for them.

At the head of the order was the clerk. He was appointed not from among the boyars, but from literate and unborn service people. This was done specifically in order to contrast the state apparatus with the boyar power and its influence. That is, the orders served the king, and not the noble nobility, who had their own interests, sometimes at odds with the state ones.

In foreign policy, the Elected Rada was oriented primarily to the east. The Astrakhan and Kazan khanates were annexed to the Moscow kingdom. In the west, the Baltic states fell into the zone of state interests. On January 17, 1558, the Livonian War began. Some members of the unofficial government opposed it. The war dragged on for 25 long years and caused a severe economic crisis (1570-1580), called Porukha.

In 1560, the unofficial government ordered long life. The reason was disagreements between Ivan the Terrible and the reformers. They accumulated for a long time, and their source lay in the exorbitant lust for power and ambitions of the Moscow Tsar. The autocrat began to feel burdened by the presence next to him of people who had independent and independent views.

While the tsarist power was weak, Ivan the Terrible tolerated the reformers and obeyed them in everything. But, thanks to competent transformations, the central apparatus has become very strong. The Tsar rose above the boyars and became a true autocrat. Adashev and the rest of the reformers began to interfere with him.

The reforms of the Elected Rada did their job - it was no longer needed. The king began to look for a reason to alienate his former friends and devoted assistants. The relationship between Sylvester and Adashev with the closest relatives of the tsar’s first and beloved wife, Anastasia Zakharova-Yuryeva, was tense. When the queen died, Ivan IV accused his former favorites of neglecting the “youth.”

Foreign policy disagreements, aggravated by the Livonian War, added fuel to the fire. But the most serious were internal political conflicts. The Elected Rada carried out very deep reforms, lasting for decades. The king needed immediate results. But the state apparatus was still poorly developed and did not know how to work quickly and efficiently.

At this stage of historical development, all the shortcomings and shortcomings of the central government could only be “corrected” by terror. The Tsar followed this path, and the reforms of the Elected Rada began to seem backward and ineffective to him.

In 1560, Sylvester was exiled to the Solovetsky Monastery. Adashev and his brother Danila went by royal decree as governors to Livonia. They were soon arrested. Adashev died in prison, and Danila was executed. In 1564, Prince Kurbsky, who led the troops in Livonia, fled to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He was on friendly terms with Adashev and understood that disgrace and execution awaited him.

The fall of the Chosen Rada marked the beginning of one of the most terrible periods of Russian history - oprichnina. The events of the first half of the 60s became its background.

“At the foundation of the Moscow state and social order were two internal contradictions, which the further, the more they made themselves felt by the Moscow people,” writes S. F. Platonov. - The first of these contradictions can be called political and defined in the words of V. O. Klyuchevsky: “This contradiction consisted in the fact that the Moscow sovereign, whom the course of history led to democratic sovereignty, had to act through a very aristocratic administration.”

Page 5 of 6

Reprisal against supporters of Adashev and Sylvester. Kurbsky's escape

A new wave of repression befell Adashev’s supporters in 1562. It was then that boyar D. Kurlyatev was forcibly tonsured a monk, Princes M.I. and A.I. Vorotynsky, Prince I.D. Belsky, boyar V.V. Morozov fell into disgrace . Daniil Adashev, the brothers of Alexei Adashev's wife Satin, and his distant relative I.F. Shishkin were executed.

Then mass executions began. Supporters of Sylvester and Adashev, all close and distant relatives of Alexei Fedorovich, many noble boyars and princes, their families, including teenage children, were either physically destroyed or sent to prison, despite their merits in the past. Karamzin exclaimed in this regard: “Moscow was frozen in fear. Blood was flowing, victims were groaning in dungeons and monasteries.” The time was coming when, in the words of the Piskarevsky Chronicler, “the sin of the earth began to multiply and oprishna began to begin.”

Now the sovereign has new favorites. Among them, the boyar Alexey Danilovich Basmanov, his handsome son Fyodor Basmanov, Prince Afanasy Ivanovich Vyazemsky and the common nobleman Grigory Lukyanovich Malyuta Skuratov-Belsky especially stood out. This last one was quite a colorful figure. Malyuta was in charge of investigation and torture for Ivan the Terrible. However, despite this, Malyuta himself was a good family man. One of his daughters, Maria, was married to an outstanding man of that time, Boris Godunov. Malyuta Skuratov died on the battlefield - the Germans cut him down on the wall of the Wittgenstein fortress in Livonia during the assault in 1573.

Mass executions caused many Moscow boyars and nobles to flee to foreign lands. In April 1564, an experienced and prominent governor, Prince Andrei Mikhailovich Kurbsky, fled from Yuriev Livonsky (now Tartu) to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. A man close to Adashev and Sylvester, Kurbsky initially escaped disgrace. But in August 1562 he lost the battle of Nevel, and only a battle wound saved the prince from reprisals. Kurbsky, however, knew that the Tsar had not forgiven him for his failure; he had heard rumors about the “angry words” of the ruler. In a message to the monks of the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery, Prince Andrei wrote that “many misfortunes and troubles” were “beginning to boil over him.” Kurbsky's flight hit Grozny even harder because the fugitive boyar sent a short but energetic message from abroad to his former monarch, in which he angrily accused the tsar of tyranny and executions of innocent people.

Ivan the Terrible was especially struck and enraged by the betrayal of Andrei Kurbsky, whom he valued not only as an honored governor and closest state adviser, but also as a personal and trusted friend. And now - an unexpected betrayal. And not just treason, but the shameful flight of the Russian governor from the battlefield to the enemy’s camp at one of the most difficult moments for Russia in its protracted war with Livonia. The Polish king graciously received Kurbsky, retained all his high honors and granted him a rich estate.

Prince Kurbsky Andrei Mikhailovich is a famous Russian politician, commander, writer and translator, the closest associate of Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible. In 1564, during the Livonian War, he fled from possible disgrace to Poland, where he was accepted into the service of King Sigismund II Augustus. Subsequently he fought against Muscovy.

Family tree

Prince Rostislav Smolensky was the grandson of Vladimir Monomakh himself and was the ancestor of two eminent families - the Smolensk and Vyazemsky families. The first of them had several branches, one of which was the Kurbsky family, who reigned in Yaroslavl from the 13th century. According to legend, this surname came from the main village called Kurby. This inheritance went to Yakov Ivanovich. All that is known about this man is that he died in 1455 on the Arsk field, bravely fighting the Kazan people. After his death, the estate passed into the possession of his brother Semyon, who served with Grand Duke Vasily.

In turn, he had two sons - Dmitry and Fyodor, who were in the service of Prince Ivan III. The last of them was the Nizhny Novgorod governor. His sons were brave warriors, but only Mikhail, who bore the nickname Karamysh, had children. Together with his brother Roman, he died in 1506 in battles near Kazan. Semyon Fedorovich also fought against the Kazan and Lithuanians. He was a boyar under Vasily III and sharply condemned the prince’s decision to tonsure his wife Solomiya as a nun.

One of Karamysh's sons, Mikhail, was often appointed to various command positions during campaigns. The last military campaign in his life was the 1545 campaign against Lithuania. He left behind two sons - Andrei and Ivan, who later successfully continued the family military traditions. Ivan Mikhailovich was seriously wounded, but did not leave the battlefield and continued to fight. It must be said that numerous injuries seriously undermined his health, and a year later he died.

An interesting fact is that no matter how many historians write about Ivan IV, they will definitely remember Andrei Mikhailovich - perhaps the most famous representative of his family and the tsar’s closest ally. Until now, researchers are arguing about who Prince Kurbsky really is: a friend or enemy of Ivan the Terrible?

Biography

No information about his childhood years has been preserved, and no one would have been able to accurately determine Andrei Mikhailovich’s date of birth if he himself had not casually mentioned it in one of his works. And he was born in the fall of 1528. It is not surprising that for the first time Prince Kurbsky, whose biography was associated with frequent military campaigns, was mentioned in documents in connection with the next campaign of 1549. In the army of Tsar Ivan IV, he had the rank of steward.

He was not yet 21 years old when he took part in the campaign against Kazan. Perhaps Kurbsky was able to immediately become famous for his military exploits on the battlefields, because a year later the sovereign made him a governor and sent him to Pronsk to protect the southeastern borders of the country. Soon, as a reward either for military merit, or for a promise to arrive at the first call with his detachment of soldiers, Ivan the Terrible granted Andrei Mikhailovich lands located near Moscow.

First victories

It is known that the Kazan Tatars, starting from the reign of Ivan III, quite often raided Russian settlements. And this despite the fact that Kazan was formally dependent on the Moscow princes. In 1552, the Russian army was again convened for another battle with the rebellious Kazan people. Around the same time, the army of the Crimean Khan appeared in the south of the state. The enemy army came close to Tula and besieged it. Tsar Ivan the Terrible decided to stay with the main forces near Kolomna, and send a 15,000-strong army commanded by Shchenyatev and Andrei Kurbsky to the rescue of the besieged city.

The Russian troops took the khan by surprise with their unexpected appearance, so he had to retreat. However, near Tula there still remained a significant detachment of Crimeans, mercilessly plundering the outskirts of the city, not suspecting that the main troops of the khan had gone to the steppe. Immediately Andrei Mikhailovich decided to attack the enemy, although he had half as many warriors. According to surviving documents, this battle lasted an hour and a half, and Prince Kurbsky emerged victorious.

The result of this battle was a large loss of enemy troops: half of the 30,000-strong detachment died during the battle, and the rest were either captured or drowned while crossing Shivoron. Kurbsky himself fought along with his subordinates, as a result of which he received several wounds. However, within a week he was back in action and even went on a hike. This time his path ran through the Ryazan lands. He was faced with the task of protecting the main forces from sudden attacks by the steppe inhabitants.

Siege of Kazan

In the autumn of 1552, Russian troops approached Kazan. Shchenyatev and Kurbsky were appointed commanders of the Right Hand regiment. Their detachments were located across the Kazanka River. This area turned out to be unprotected, so the regiment suffered heavy losses as a result of fire opened at them from the city. In addition, Russian soldiers had to repel attacks by the Cheremis, who often came from the rear.

On September 2, the assault on Kazan began, during which Prince Kurbsky and his warriors had to stand on the Elbugin Gate so that the besieged would not be able to escape from the city. Numerous attempts by enemy troops to break through the guarded area were largely repulsed. Only a small part of the enemy soldiers managed to escape from the fortress. Andrei Mikhailovich and his soldiers rushed in pursuit. He fought bravely, and only a serious wound forced him to finally leave the battlefield.

Two years later, Kurbsky again went to the Kazan lands, this time to pacify the rebels. It must be said that the campaign turned out to be very difficult, since the troops had to make their way off-road and fight in wooded areas, but the prince coped with the task, after which he returned to the capital with victory. It was for this feat that Ivan the Terrible promoted him to boyar.

At this time, Prince Kurbsky was one of the people closest to Tsar Ivan IV. Gradually, he became close to Adashev and Sylvester, representatives of the reformer party, and also became one of the sovereign’s advisers, entering the Elected Rada. In 1556, he took part in a new military campaign against the Cheremis and again returned from the campaign as a winner. First, he was appointed governor of the Left Hand regiment, which was stationed in Kaluga, and a little later he took command of the Right Hand regiment, located in Kashira.

War with Livonia

It was this circumstance that forced Andrei Mikhailovich to return to combat formation again. At first he was appointed to command the Storozhevoy, and a little later the Advanced Regiment, with which he took part in the capture of Yuriev and Neuhaus. In the spring of 1559, he returned to Moscow, where they soon decided to send him to serve on the southern border of the state.

The victorious war with Livonia did not last long. When failures began to fall one after another, the tsar summoned Kurbsky and made him commander of the entire army fighting in Livonia. It must be said that the new commander immediately began to act decisively. Without waiting for the main forces, he was the first to attack the enemy detachment, located not far from Weissenstein, and won a convincing victory.

Without thinking twice, Prince Kurbsky makes a new decision - to fight the enemy troops, which were personally led by the master of the famous Livonian Order himself. Russian troops bypassed the enemy from the rear and, despite the night time, attacked him. Soon the firefight with the Livonians escalated into hand-to-hand combat. And here the victory was for Kurbsky. After a ten-day respite, the Russian troops moved on.

Having reached Fellin, the prince ordered to burn its outskirts and then begin a siege of the city. In this battle, Landmarshal of the Order F. Schall von Belle, who was rushing to help the besieged, was captured. He was immediately sent to Moscow with a covering letter from Kurbsky. In it, Andrei Mikhailovich asked not to kill the land marshal, since he considered him an intelligent, brave and courageous person. This message suggests that the Russian prince was a noble warrior who not only knew how to fight well, but also treated worthy opponents with great respect. However, despite this, Ivan the Terrible still executed the Livonian. Yes, this is not surprising, since around the same time the government of Adashev and Sylvester was eliminated, and the advisers themselves, their associates and friends were executed.

Defeat

Andrei Mikhailovich took Fellin Castle in three weeks, after which he went to Vitebsk, and then to Nevel. Here luck turned against him and he was defeated. However, the royal correspondence with Prince Kurbsky indicates that Ivan IV did not intend to accuse him of treason. The king was not angry with him for his unsuccessful attempt to capture the city of Helmet. The fact is that if this event had been given great importance, then this would have been mentioned in one of the letters.

Nevertheless, it was then that the prince first thought about what would happen to him when the king learned of the failures that had befallen him. Knowing well the strong character of the ruler, he understood perfectly well: if he defeats his enemies, nothing will threaten him, but in case of defeat he can quickly fall out of favor and end up on the chopping block. Although, in truth, apart from compassion for the disgraced, there was nothing to blame him for.

Judging by the fact that after the defeat at Nevel, Ivan IV appointed Andrei Mikhailovich as governor of Yuryev, the tsar did not intend to punish him. However, Prince Kurbsky fled to Poland from the tsar’s wrath, as he felt that sooner or later the sovereign’s wrath would fall on his head. The king highly valued the prince’s military exploits, so he once called him into his service, promising him a good reception and a luxurious life.

Escape

Kurbsky increasingly began to think about the proposal until, at the end of April 1564, he decided to secretly flee to Volmar. His followers and even servants went with him. Sigismund II received them well, and rewarded the prince himself with estates with the right of inheritance.

Having learned that Prince Kurbsky had fled from the tsar's wrath, Ivan the Terrible unleashed all his rage on the relatives of Andrei Mikhailovich who remained here. All of them suffered a difficult fate. To justify his cruelty, he accused Kurbsky of treason, violating the kiss of the cross, as well as kidnapping his wife Anastasia and wanting to reign in Yaroslavl himself. Ivan IV was able to prove only the first two facts, but he clearly invented the rest in order to justify his actions in the eyes of Lithuanian and Polish nobles.

Life in exile

Having entered the service of King Sigismund II, Kurbsky almost immediately began to occupy high military positions. Less than six months later, he already fought against Muscovy. With Lithuanian troops he took part in the campaign against Velikie Luki and defended Volyn from the Tatars. In 1576, Andrei Mikhailovich commanded a large detachment that was part of the troops of the Grand Duke who fought with the Russian army near Polotsk.

In Poland, Kurbsky lived almost all the time in Milyanovichi, near Kovel. He entrusted the management of his lands to trusted persons. In his free time from military campaigns, he was engaged in scientific research, giving preference to works on mathematics, astronomy, philosophy and theology, as well as studying Greek and Latin.

It is a known fact that the fugitive Prince Kurbsky and Ivan the Terrible corresponded. The first letter was sent to the king in 1564. He was brought to Moscow by Andrei Mikhailovich’s faithful servant Vasily Shibanov, who was subsequently tortured and executed. In his messages, the prince expressed his deep indignation at those unjust persecutions, as well as the numerous executions of innocent people who served the sovereign faithfully. In turn, Ivan IV defended the absolute right to pardon or execute any of his subjects at his own discretion.

The correspondence between the two opponents lasted for 15 years and ended in 1579. The letters themselves, the well-known pamphlet entitled “The History of the Grand Duke of Moscow” and the rest of Kurbsky’s works are written in literate literary language. In addition, they contain very valuable information about the era of the reign of one of the most cruel rulers in Russian history.

Already living in Poland, the prince married a second time. In 1571, he married the rich widow Kozinskaya. However, this marriage did not last long and ended in divorce. For the third time, Kurbsky married a poor woman named Semashko. From this union the prince had a son and daughter.

Shortly before his death, the prince took part in another campaign against Moscow under the leadership of But this time he did not have to fight - having reached almost the border with Russia, he became seriously ill and was forced to turn back. Andrei Mikhailovich died in 1583. He was buried on the territory of the monastery located near Kovel.

All his life he was an ardent supporter of Orthodoxy. Kurbsky's proud, stern and irreconcilable character greatly contributed to the fact that he had many enemies among the Lithuanian and Polish nobility. He constantly quarreled with his neighbors and often seized their lands, and covered the royal envoys with Russian abuse.

Soon after the death of Andrei Kurbsky, his confidant, Prince Konstantin Ostrozhsky, also died. From that moment on, the Polish government began to gradually take away the property from his widow and son, until finally it took Kovel too. Court hearings on this matter lasted several years. As a result, his son Dmitry managed to return part of the lost lands, after which he converted to Catholicism.

Opinions about him as a politician and a person are often diametrically opposed. Some consider him an inveterate conservative with an extremely narrow and limited outlook, who supported the boyars in everything and opposed the tsarist autocracy. In addition, his flight to Poland is regarded as a kind of prudence associated with the great worldly benefits that King Sigismund Augustus promised him. Andrei Kurbsky is even suspected of the insincerity of his judgments, which he set out in numerous works that were entirely aimed at maintaining Orthodoxy.

Many historians are inclined to think that the prince was, after all, an extremely intelligent and educated man, as well as sincere and honest, always on the side of good and justice. For such character traits they began to call him “the first Russian dissident.” Since the reasons for the disagreement between him and Ivan the Terrible, as well as the legends of Prince Kurbsky themselves, have not been fully studied, the controversy over the personality of this famous political figure of that time will continue for a long time.

The well-known Polish heraldist and historian Simon Okolsky, who lived in the 17th century, also expressed his opinion on this issue. His description of Prince Kurbsky boiled down to the following: he was a truly great man, and not only because he was related to the royal house and occupied the highest military and government positions, but also because of his valor, since he won several significant victories . In addition, the historian wrote about the prince as a truly happy person. Judge for yourself: he, an exile and fugitive boyar, was received with extraordinary honors by the Polish king Sigismund II Augustus.

Until now, the reasons for the flight and betrayal of Prince Kurbsky are of keen interest to researchers, since the personality of this man is ambiguous and multifaceted. Another proof that Andrei Mikhailovich had a remarkable mind can be served by the fact that, being no longer young, he managed to learn the Latin language, which until that time he did not know at all.

In the first volume of the book called Orbis Poloni, which was published in 1641 in Krakow, the same Simon Okolsky placed the coat of arms of the Kurbsky princes (in the Polish version - Krupsky) and gave an explanation for it. He believed that this heraldic sign was Russian in origin. It is worth noting that in the Middle Ages the image of a lion could often be found on the coats of arms of the nobility in different states. In ancient Russian heraldry, this animal was considered a symbol of nobility, courage, moral and military virtues. Therefore, it is not surprising that it was the lion that was depicted on the princely coat of arms of the Kurbskys.